Tom Junod despre jurnalism, reguli ÅŸi poveÅŸti

Nu e un secret că Tom Junod e scriitorul meu preferat. Spun scriitor și nu jurnalist pentru că Junod are o relație ambivalentă cu acest termen. Prin preferat înțeleg următoarele: când apare ceva nou de Tom Junod pun totul deoparte și mă apuc să citesc. De ce? Pentru că îmi oferă garanția unei experiențe memorabile și unor trăiri puternice. Deseori, modul în care omul filtrează realitatea face ficțiunea modernă să pară un simplu exercițiu de imaginație.

N-are rost să continui – mai bine îl las pe maestru să vorbească. Ce urmează este textul integral al unui discurs fabulos ținut de Junod la Missouri School of Journalism, în martie 2009. Tema este viitorul poveștilor într-o lumea twitterată, dar această descriere grosieră nu face decât să submineze experiența lecturii acestui discurs.

După ce terminați de citit, nu uitați să spuneți cum a fost.

* Tom Junod s-a năcut în 1958 și scrie în prezent pentru Esquire. A câștigat două National Magazine Awards și a fost finalist de alte zece ori, cel mai recent pentru un portret făcut lui Steve Jobs. Citiți cu încredere și textele lui despre Norman Mailer, cuvântul “crimă”, băieții răi și gura lui Hillary Clinton.

——————————————————–

Tom Junod’s Keynote Speech

Missouri Association of Publications annual meeting

Missouri School of Journalism, March 2009

Hello everyone. Thanks for having me, and thanks, John, for your kind introduction.

You know, I have to admit, I”™ve been agonizing over what to say here today.

Not because of a lack of anything to say, not because there”™s not much to talk about, and not even because I didn”™t go to journalism school and have been railing against J-schools in general for so long and so hard that I feel slightly disingenuous standing here and addressing you from this podium on the invitation of one of the most highly prestigious ones.

No, I”™ve been agonizing because, well, we live in momentous times. If anything, there is too much to say, and I”™ve found that rather than standing against the values imparted by J-school educations ““ as I have always told myself that I have ““ my 22 years of writing for magazines have made me rather more conventional than I think I am. I have always complained about journalism and its restrictions, I have always looked at journalism ““ both its vaguely defined sense of rules and regulations, and its rather arrogant self of itself as a profession, instead of a trade – as a problem to be overcome, rather than a religion to be practiced. But now that the whole thing is threatened, it turns out that I like journalism quite a bit. You could even say that I miss it pre-emptively.

Moartea unui keyboard

Întâi au cedat tastele din partea dreaptă, în special “M” și “O”. Probabil era de la cafeaua vărsată înainte să vină căldura, așa că am strecurat un servețel de șters ochelarii între taste și am încercat să remediez problema. A mers. Dar apoi, acum două zile, a cedat SPACE-ul. Întâi a început să lenevească apăsat. Apoi rămânea blocat până la următoarea bătaie, chiar următoarele două. I-am desfăcut toate cele 20 de șuruburi, dar pe partea pe care am intrat nu puteam accesa tumoarea. Am încercat să intru sub SPACE cu șervețele, bețigase, vrăji și îndemnuri, dar degeaba.

Keyboard-ul alb, Ultra, cu care am scris aproape fiecare text în ultimii doi ani – cu siguranță toate cele mai lungi de 1.000 de cuvinte – a murit. Această imagine e fotografia de despărțire, făcută înainte să-l îndes într-o cutie cu destinația gunoi.

Acest post e scris cu un keyboard nou, un Samsung Pleomax PKB-750B, simplu, fără butoane multimedia și porturi USB. Cea mai mare diferență e culoarea. Am stat zece minute în Diverta să mă întreb dacă un keyboard negru scrie altfel decât un keyboard alb.

E o treabă serioasă asta cu micile schimbări de mediu. Bine, nu așa de serioasă cum ar fi o schimbare de tipul trecerii de la hârtie la keyboard:

[John] Updike was probably the very first New Yorker writer to shift over to a computer, back in the early eighties. “œI don”™t know how this will change my writing,” he wrote to me in advance, “œbut it will.” He was right, of course: the flavor was mysteriously different, the same wine but of another year. (Roger Angell despre Updike)

Tastele sunt ceva mai silențioase, dar parcă dornice să arate că pot și ele produce. Să vedem. Chiar am mare nevoie de ele weekend-ul ăsta.

Puţin despre atelierele de scriitură

Inițial voiam să postez încă un text despre Islanda (și cum a falimentat), scris în aceeași perioadă ca și cel din Vanity Fair, dar The New Yorker n-a încărcat decât o descriere. Lecția era că un text nu e niciodată scris până nu-l scrii (și) tu. Diferențele de ton și abordare dintre Michael Lewis și Ian Parker sunt palpabile și chiar dacă VF și New Yorker fac parte din același trust nu înseamnă că au aceiași cititori. În România auzi prea des spunându-se: “ah, păi X a apărut luna trecută în Y”. Dar asta e o poveste pentru mai târziu.

Rămânând totuși la The New Yorker, vă recomand un text despre predat scriitură, mai precis despre cursurile și programele academice de creative writing. E mai degrabă vorba de predat ficțiune aici, dar stilul de lucru în atelier e folosit și la unele cursuri de jurnalism (mai ales în cele de scriitură de revistă).

La master am trecut printr-un astfel de curs și a fost probabil modelul pe care l-am folosit – inconștient sau nu – în cursurile pe care le-am ținut de la CJI. Probabil de aceea s-a șoptit ocazional că grupurile de acolo erau “secte”. O astfel de interacțiune preferă dialogul în locul prelegerii, iar învățarea se face din interațiunea cu cei din jur – da, un fel de terapie de grup. Întrebarea “se poate învăța scrisul?” e elefantul care bântuie aceaste adunări, neaducând deobicei prea multe răspunsuri afirmative.

Cum funcționează un astfel de atelier?

The workshop is a process, an unscripted performance space, a regime for forcing people to do two things that are fundamentally contrary to human nature: actually write stuff (as opposed to planning to write stuff very, very soon), and then sit there while strangers tear it apart. There is one person in the room, the instructor, who has (usually) published a poem. But workshop protocol requires the instructor to shepherd the discussion, not to lead it, and in any case the instructor is either a product of the same process””a person with an academic degree in creative writing””or a successful writer who has had no training as a teacher of anything, and who is probably grimly or jovially skeptical of the premise on which the whole enterprise is based: that creative writing is something that can be taught.

Grosul textului lui Louis Menand e despre programele americane de creative writing – ce funcționează, ce nu, dacă izolează scriitorii sau dacă, dimpotrivă, îi ancorează în timpurile în care trăiesc etc. Finalul însă e universal. Concluzia – personală – a lui Menand e că atelierele de scriitură funcționează – nu te învăță neapărat cum să scrii, dar te învață că trebuie să scrii dacă asta îți dorești. Și te învață că nu ești singurul care se luptă cu incertitudini și probleme:

[In] spite of all the reasons that they shouldn”™t, workshops work. I wrote poetry in college, and I was in a lot of workshops. I was a pretty untalented poet, but I was in a class with some very talented ones, including Garrett Hongo, who later directed the creative-writing program at the University of Oregon, and Brenda Hillman, who teaches in the M.F.A. program at St. Mary”™s College, in California. Our teacher was a kind of Southern California Beat named Dick Barnes, a sly and wonderful poet who also taught medieval and Renaissance literature, and who could present well the great stone face of the hard-to-please. I”™m sure that our undergraduate exchanges were callow enough, but my friends and I lived for poetry. We read the little magazines””Kayak and Big Table and Lillabulero””and we thought that discovering a new poet or a new poem was the most exciting thing in the world. When you are nineteen years old, it can be.

Did I engage in self-observation and other acts of modernist reflexivity? Not much. Was I concerned about belonging to an outside contained on the inside? I don”™t think it ever occurred to me. I just thought that this stuff mattered more than anything else, and being around other people who felt the same way, in a setting where all we were required to do was to talk about each other”™s poems, seemed like a great place to be. I don”™t think the workshops taught me too much about craft, but they did teach me about the importance of making things, not just reading things. You care about things that you make, and that makes it easier to care about things that other people make.

And if students, however inexperienced and ignorant they may be, care about the same things, they do learn from each other. I stopped writing poetry after I graduated, and I never published a poem””which places me with the majority of people who have taken a creative-writing class. But I”™m sure that the experience of being caught up in this small and fragile enterprise, contemporary poetry, among other people who were caught up in it, too, affected choices I made in life long after I left college. I wouldn”™t trade it for anything.

Scott Dadich despre Wired şi design de publicaţie

De ceva vreme citesc despre o prezentare pe care Scott Dadich, creative director la Wired și președinte SPD, a ținut-o în această primăvara prin lume (SUA, Anglia, Australia etc.) Din fericire, australienii s-au gândit s-o înregistreze și să dea clipul la televizor (și de acolo, online). Cele trei părți ale prezentării – în care Dadich explică principiile grafice ale revistei și secțiunilor ei – iau numele a trei porunci de lucru pe care Dadich le urmează:

- Details matter.

- Evolution, not revolution.

- Constraint is freedom

Câți designeri de publicații de la noi lucrează oare ca Dadich? Ray ar spune că nu prea mulți. (Și nu ține doar de resurse)

Am mai scris despre Wired aici, aici și – mai ales! – aici.

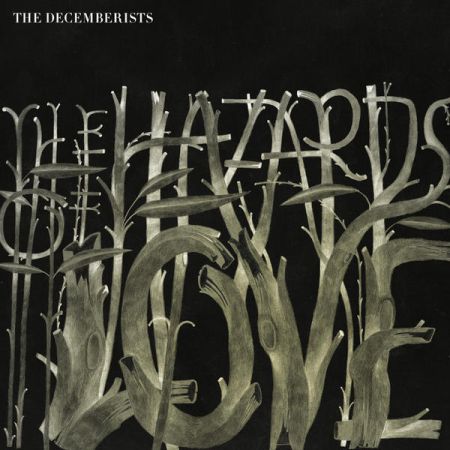

The Decemberists ÅŸi poveÅŸtile muzicale

Astăzi se lansează oficial noul album The Decemberists, The Hazards of Love. Da, The Decemberists e formația mea preferată, dar ăsta nu e singurul motiv pentru care citiți acest post. The Decemberists spun povești în cântecele lor – de cele mai multe ori triste și populate de personaje dintr-un trecut nedefinit, aproape picaresc.

Albumul precedent, The Crane Wife, a fost inspirat de o poveste japoneză de dragoste dintre un bărbat sărac și femeia care-l îmbogățește țesând haine scumpe din propriile pene (ea fiind de fapt cocorul rănit pe care bărbatul îl tratase la un moment dat). The Hazards of Love spune povestea arhetipală de dragoste interzisă dintre Margaret și William și forțele care încearcă să-i separe.

Dacă n-ați ascultat/văzut The Decemberists, puteți începe cu “O Valencia” și “Sixteen Military Wives” și apoi puteți trece la un concert întreg, înregistrat de NPR săptămâna trecută la SXSW 2009:

Veşti despre narativul românesc

La sfârșitul anului trecut, am fost invitat să scriu un text despre jurnalismul narativ în România pentru newsletter-ul de primăvară al International Association for Literary Journalism Studies (IALJS), o asociație de profesori și cercetători din lumea întreagă.

Textul îl puteți găsi atât în newsletterul asociației (aici), cât și în continuare acestui post.

Notă: Articolul Gabrielei la care textul meu face referință – Șaișpe – îl puteți citi aici. Mai multe despre cum a fost făcut (plus jurnal de poveste), aici.

Lectură de boală – un tratament narativ

Scos puțin din uz de o răceală, am folosit statul în pat ca să citesc. Am citit din gigantul cu texte istorice, am reușit să subțiez teancul de New Yorker-uri care stăteau necitite lângă pat și am mai bifat câteva dintre textele care s-au luptat pentru premii anul trecut la National Magazine Awards. O scurtă selecție pentru cei care plănuiesc două-trei zile de zăcut și nu știu ce non-ficțiune de calitate să citească:

* My Favorite Teacher, Robert Kurson. Kurson e autorul unuia dintre textele mele preferate. În “My Favorite Teacher”, încearcă să înțeleagă motivele pentru care îl admira și îl admiră încă (oarecum) pe profesorul lui de biologie din școală, un domn ciudat, ulterior condamnat la închisoare pe viață pentru omor.

* What Do You Think of Ted Williams Now?, Richard Ben Cramer. Publicat în 1986, textul e printre cele mai bune șapte bucăți apărute vreodată în Esquire. Cramer, cunoscut pentru stilul exhaustiv de documentare, face portretul unui om care a vrut să fie cel mai bun – atât în baseball (a jucat 21 de sezoane în MLB), cât și mai târziu în pescuit. Asta în ciuda furiei care l-a consumat întreaga viață.

* Chef on the Edge, Larissa MacFarquhar. Textul ăsta m-a făcut să visez (din nou) la un restaurant. MacFarquhar face portretul lui David Chang, un chef tânăr și manical, care are trei restaurante în New York și pentru care munca lui e cel mai important lucru din lume. “You guys have to ask yourself as cooks, how bad do you want this? Life and death is what it means to me.”

* City of Fear, William Langewiesche. Langewiesche e genul de reporter care merge în locurile din care majoritatea încearcă să scape. În acest text, autorul investighează o serie de atacuri armate ce au avut loc în mai 2006 pe străzile din Sao Paolo și folosește această ocazie să pună o întrebare amețitoare: ce faci când e limpede că statul nu te mai poate proteja?

Despre ce scriem

Pe Gay Talese nu mi-l pot imagina decât îmbrăcat într-un costum cu croială impecabilă, vorbind despre poveștile din jur în felul acela așezat și senin care te face să vezi cât de mult crede în jurnalismul pe care-l face. În cazul lui, narativ. Totul pare să se rezume la: “You don”™t have to make anything up””because life is fantastic. Ordinary life is extraordinary. It is. You know this. It”™s just a matter of being able to see it, to see it and being able to write it.”

În 2006 The Morning News a publicat un interviu amplu cu Talese, în care vorbește despre obiceiul de a merge la restaurant pentru a observa oamenii, la modul lui de a căuta și a găsi povești.

Un exemplu. În 1999, 90.000 de oameni s-au dus la finala mondială de fotbal feminin dintre SUA și China. Printre ei, și Talese, care nu înțelegea mai nimic din fotbalul european și era acolo mai mult ca să vadă ce-i cu toată agitația. La final, când s-au dat lovituri de 11 metri, o singură jucătoare a ratat-o pe a ei: o chinezoaică de 24 de ani, iar Talese a știut că dacă e o poveste de spus acolo, cheia se află la acea femeie. Raționamentul care a urmat meciului este expus în interviu și arată cât de mult o potențială poveste aprinde imaginația unui om care scrie și cum se pot naște marile idei.

Și încă ceva: Talese a plecat de la NYT când avea 32 de ani, pentru că voia să dedice mai mult timp reportingului și scrisului despre oameni ale căror vieți și acțiuni înglobează sensuri mult mai profunde decât cele căutate de o știre ““ niște everymen. A arătat mereu că piedicile ar trebui să conteze mai puțin decât posibilitățile și a reușit să scrie unele dintre cele mai frumoase bucăți din istoria jurnalismului narativ. Iată de ce:

—

When I was 24, they were saying the same thing. I teach courses and the writers say, “œOh, I don”™t think you”™d get these stories in the paper today as you did back when you were doing this thing, back in 1958, let”™s say.” In 1958 I was having trouble getting in the paper. In 2006 you”™ll have trouble. But that doesn”™t mean that you can”™t do it. You are not going to bat a thousand. You may not even be a .500 hitter. Let”™s say you get four out of 10″”but it”™s worth it. Because those four, if you get four good ones, those stories are stories that you will like to read a month from now. Or maybe a year from now. The stories that you have trouble getting in the paper are difficult because they do not fit the conventional mold of the rounded-headed editor. And if you wanted to play games with the editors you are going to wind up being an editor, someday being miserable.

Better that you should take the chance of trying something that is close to your heart, you think is what you want to write, and if they do not publish it, put it in your drawer. But maybe another day will come and you will find a place to put that. You will take it out of your drawer and do something else with it. I wrote a whole book when I was 24, I wrote a book called New York: A Serendipiter”™s Journey. It was my first published work. It was a slender volume and I got a photographer friend to illustrate some of those stories.

And these stories mainly, were stories that had been rejected by the New York Times city editor. Why? Because they didn”™t seem to have any meaning. They didn”™t make any sense. They weren”™t relevant. And I said, “œBy whose standard not relevant?” I am writing about people who are alive in the city of New York during mid-20th-century America. And these people are like a character in a play or they are figures in a short story or a novel. They are the sort of people that Arthur Miller wrote about when he wrote Death of a Salesman. Don”™t tell me Willy Loman is not significant. Don”™t tell me Willy Loman isn”™t important. Yes, he is not a great salesman but I know a lot of people who are not great salesmen, who weren”™t newsworthy and don”™t have a face that people recognized. But they could be given a face by the writer, they could be brought alive like Mr. Willy Loman is brought alive, not only for American audiences but all over the world. You find Willy Loman in China, you find him in India. In New Zealand. This play by Miller, such a play that it is an international play. And what is it about? A guy that didn”™t make it. You know, his wife says to his children, “œAttention must be paid.” Well, I think attention must be paid, as the great Arthur Miller said, in his play, to a lot of people who aren”™t having any attention paid to them. So the city editor tells me, “œOh, we aren”™t going to print that, they spiked it.” You know what “œspiked” means. Well, you let it be spiked and pull it off the spike and you think about it and there will come a day that attention must be paid and you will get it printed. So I say to the student of 2006, no less than the student I used to be in 1958, you have to do what you have to do with what you see, and you have a way of seeing people and caring about people and describing your city, describing what you see. It is your realm, your world. And you do it. Nobody is going to like it, necessarily, but you do it.

– Gabi

Bilanţ

Cei care au participat la atelierul de toamnă de la CJI (un fel de modul pentru avansați al cursului obișnuit) au avut un scop precis în cele trei weekend-uri în care ne-am întâlnit: să încerce să ducă la capăt o poveste și să încerce să o publice. Acum, la aproape două luni de când ne-am despărțit, se poate face un mic bilanț.

Din cei 11 participanți, unul a fost “absolvit” de obligația de a scrie un text și transformat într-un al doilea editor. Din cei 10 care au muncit la o poveste, o bună parte și-au schimbat ideea cu care veniseră pentru că nu era fezabilă. (Pont: cu cât mai mică e povestea, cu atât ai mai multe șanse să-ți iasă).

Șapte din cele 10 texte au fost finalizate până în acest moment. Trei – din câte știu – sunt încă în stadiul de documentare. Iată ce s-a întâmplat, sau se va întâmpla, cu cele șapte: (Vă împărtășesc soarta lor ca să vedeți că nu glumeam când spuneam că – în ciuda crizei, lipsei de spațiu, fondurilor etc. – trăim vremuri bune pentru jurnalismul narativ):

– portretul ministrului culturii, Theodor Paleologu, a apărut în numărul de ianuarie-februarie al Esquire.

– portretul Mariei Costache, graficiana de la RomâniaFilm, a apărut în numărul din februarie al Tabu.

– despre cum se adună publicul care aplaudă la emisiuni TV (și cine face treaba asta), ați putut citi pe HotNews.

– de ieri, găsiți pe 9AM, povestea primului turneu prin care a trecut Marius Crăciun după ce a devenit campion mondial la jocul FIFA.

– celelalte trei texte, despre care vă voi spune mai multe în momentul în care vor apărea, le veți găsi în curând în Esquire, Tabu și într-un număr viitor al revistei Pilot Magazin.

Dacă trebuie să ÅŸtii sigur… nu scrie

Nu mă pricep la poezie, dar simt nevoia să împărtășesc aceste versuri. W.S. Merwin e un poet american ultra-premiat, iar această poezie este despre John Berryman, care i-a fost mentor și profesor. Și, bineînțeles, e un poem despre scris, despre așteptări și despre nevoia de nesiguranță. (Via un editor de la Details).

Berryman

I will tell you what he told me

in the years just after the war

as we then called

the second world war

don’t lose your arrogance yet he said

you can do that when you’re older

lose it too soon and you may

merely replace it with vanity

just one time he suggested

changing the usual order

of the same words in a line of verse

why point out a thing twice

he suggested I pray to the Muse

get down on my knees and pray

right there in the corner and he

said he meant it literally

it was in the days before the beard

and the drink but he was deep

in tides of his own through which he sailed

chin sideways and head tilted like a tacking sloop

he was far older than the dates allowed for

much older than I was he was in his thirties

he snapped down his nose with an accent

I think he had affected in England

as for publishing he advised me

to paper my wall with rejection slips

his lips and the bones of his long fingers trembled

with the vehemence of his views about poetry

he said the great presence

that permitted everything and transmuted it

in poetry was passion

passion was genius and he praised movement and invention

I had hardly begun to read

I asked how can you ever be sure

that what you write is really

any good at all and he said you can’t

you can’t you can never be sure

you die without knowing

whether anything you wrote was any good

if you have to be sure don’t write

– William Stanley Merwin